The Languages of Plants

“Plants seem to have a language of their own, with which they communicate to us their medicinal properties. In turn, humans have developed various ways of transmitting plant lore, knowledge and medicinal uses of herbs and other plants.” - Beti Scott, Movement in Thyme.

By Beti Scott | Illustrations by Indre Šimkutė

The Victorians devised a secret code, a language of flowers, by which they could transmit secret messages between those in-the-know. Specific flowers carried different meanings, and combined in posies–or to use the parlance of the times tussie-mussies–could convey secret love, gratitude, friendship, even rejection.

The language of plants goes deeper than simply their use as props in illicit affairs of the heart. Plants seem to have a language of their own, with which they communicate to us their medicinal properties. In turn, humans have developed various ways of transmitting plant lore, knowledge and medicinal uses of herbs and other plants.

The following plants can all be found in Queen’s Park and demonstrate some of the webs of communication between plants and humans:

The dandelion and its healing properties, illustrated.

Dandelion

Taraxacum officinale

Chew on a fresh leaf. It's bitter, and increases saliva production. This communicates one of dandelion leaf’s main medicinal actions, stimulating the digestive system allowing the water to digest food more efficiently.

Folk names for dandelion include cankerwort referring to the folk use of the sap from its stems to treat warts and cankers; dents-de-lion in French or lion's tooth in English, describing the shape of the leaves – a handy reminder for plant identification. Also in French, another name – pis en lit – translates to ‘wet the bed’ referring to the leaf's affinity for the kidneys and urinary system.

Rowan

Sorbus aucuparia

Folk names for plants also tell us cultural and spiritual practices and associations. In Gaelic, rowan is known as fuinnseag-coille which translates to ‘wood enchantress’. In Scotland and Ireland in particular, rowan has long been associated with witches, not least because of the five-pointed star that appears on each berry. Rowan is known as a witches’ tree and as a tree to protect against witches. Tradition holds that a beam of rowan wood above the hearth will protect a household from dark forces, but to fell a rowan tree is to bring curses upon yourself.

In Viking mythology it was believed that the first woman grew from a rowan tree. In Celtic mythology, it is a symbol of Brigid, who is the Celtic goddess, turned Christian saint, of midwifery, weavers and healers among other things. Rowan berries are still used in protective magic, dried as beads to make garlands and jewellery, as well as medicinally in syrups and jams to support the immune system.

The dandelion and its healing properties, illustrated.

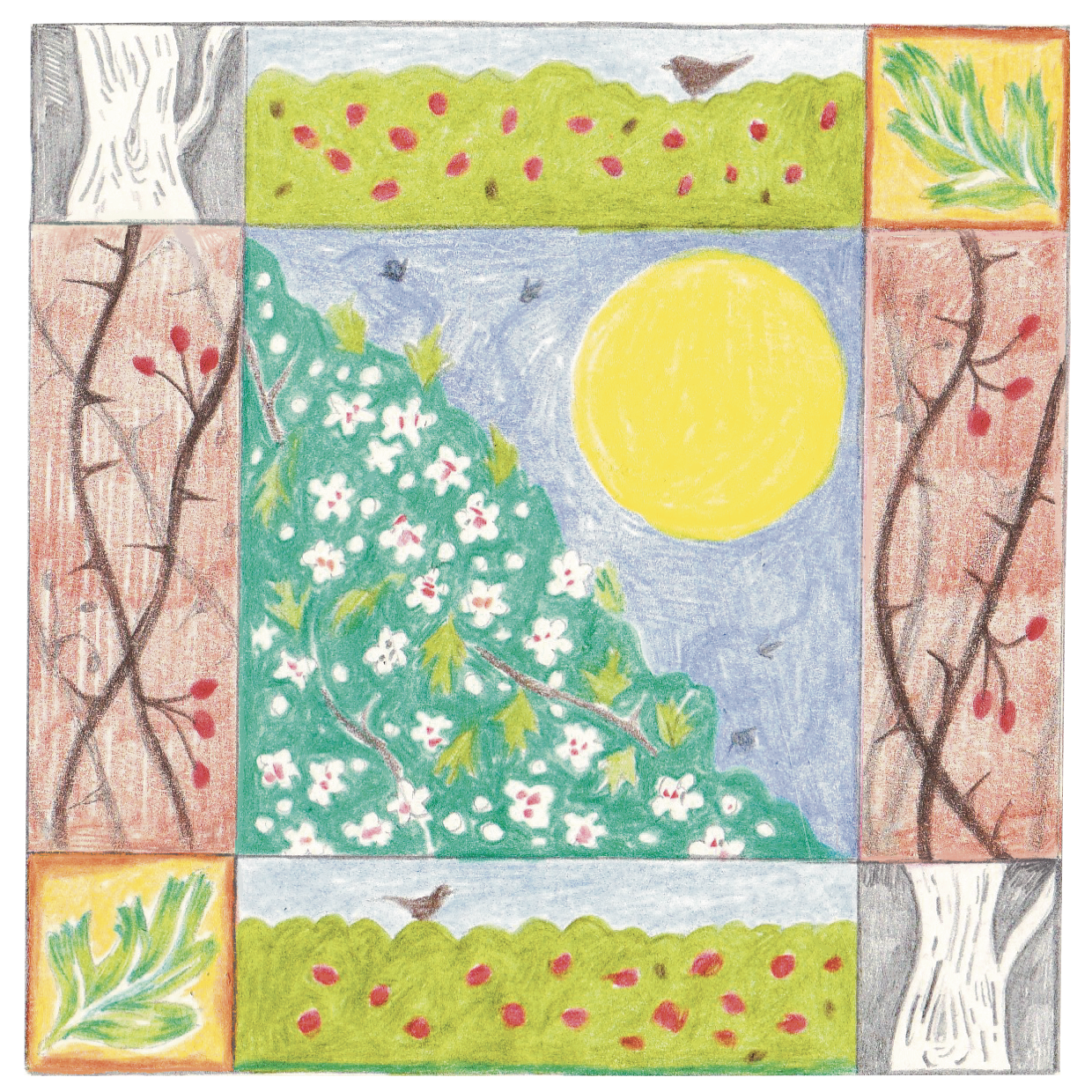

Hawthorn

Crataegus monogyna

Like the rowan, hawthorn is steeped in folk tales and beliefs that communicate wisdom through the ages, including a prohibition against the felling of a hawthorn, lest you anger the fairy folk that live in it. This belief is particularly prevalent in Ireland, hawthorn trees are often left in fields where other trees have been removed.

A taxi driver once told me “dinnae cast a clout ‘til the may is out”– commonly misunderstood by gardeners to mean don’t plant out seedlings until the end of the month of may. But the ‘may’ actually refers to the flowers of the hawthorn tree, which are also known as may flowers or may blossoms.

Tradition holds you should not bring may blossoms into the house, or else risk inviting death in. Although the small, white flowers of the hawthorn are dainty and sweet looking, the association with death is unsurprising when you smell them – they contain a chemical called trimethylamine which is present in decaying flesh. To the human nose, this is like foul language, an olfactory swear word, but to an insect pollinator of hawthorn, the smell of death is an enticing love note, a whispered sweet nothing. Another association that ties hawthorn to death is the theory that the crown of thorns worn by Christ during his crucifixion is thought by some to be made of hawthorn.

Rose plant and its healing properties, illustrated.

Rose

Rosa sp.

Rose too, is famed for its thorns, which feature in everything from fairy tales to pop songs. The contrast between the pillowy petals and enticing scent with the pain of a prick makes the rose an enduring metaphor. With so many varieties of rose, there was even a distinct dialect within the Victorian language of flowers, with the wild or dog rose (Rosa canina) standing for pleasure and pain.

When foraging, either for the heady-scented petals or nutrient rich hips of the rose plant, thorns remind us to practice ethical foraging, not taking too much, while leaving some for the birds, insect and other non-human friends, and listening to the plants “no” when we get pricked, taking that as a sign to move onto the next plant. In this way, roses assert their own boundaries. Rose’s medicine in turn supports our boundaries, either as an astringent, shoring up our body tissues’ integrity to protect us from pathogens or on a more emotional and spiritual level, allowing us to take heart.

Another way rose – particularly rosehips – communicate with us is through the language of colour. Rosehips come in many shades, from bright orange to almost black, and the hue gives us an insight into the particular chemical makeup of the fruit, orange tends to be high in vitamin C –and darker tends to be higher in antioxidants.

Yarrow plant and its healing properties, illustrated.

Yarrow

Achillea millefolium

Yarrow’s appearance, like many plants including the berries mentioned above, gives clues to some of its medicinal uses. The feathery, fern like leaves not only gives it the millefolium (meaning thousand leaves) name, but the fractal patterns of the leaves when closely studied bring to mind the knitting together of tissues, or in fact the circulatory system within the body. Yarrow is used commonly as a first aid herb for wounds for it’s ability to purify the blood, staunch excessive bleeding and support tissue healing.

This phenomena, of plants looking like the body parts and systems they are used to treat is known as the doctrine of signatures. Whether clues left by the Creator, as has been believed in many healing traditions, a handy mnemonic device for budding herbalists, or direct communication from the plants themselves, examples include the appearance of tiny eyes within the flower of the eyebright plant, which can be used to treat conjunctivitis, irritation of the eye and streaming eyes from allergies; the brain-like appearance of walnuts which contain omega-3 fatty acids which can support cognitive function and the glossy, erect strands of the horsetail plant which contains silica which supports with musculoskeletal issues as well as making hair glossy and strong.

Beti Scott and Indre Šimkutė are facilitators with Movement In Thyme CIC which aims to build sustainable, resilient communities, improve mental and physical wellbeing and reduce social isolation through herbal medicine, community workshops, movement activities and gardening. They run workshops and a Community Apothecary where you can pick up herbal remedies on a pay-what-you-can basis. Find them on social media @movement_in_thyme for more.