City of Empire: I See Your History

City of Empire is a new community-led exhibition at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum that uncovers Glasgow’s deep-rooted links to empire and slavery. Zara Grew met up with the exhibition's Community Curator to find out more.

Rani of Jhansi by Ramu and Shubho Karmakar

By Zara Grew | Photographs by Miriam Ali

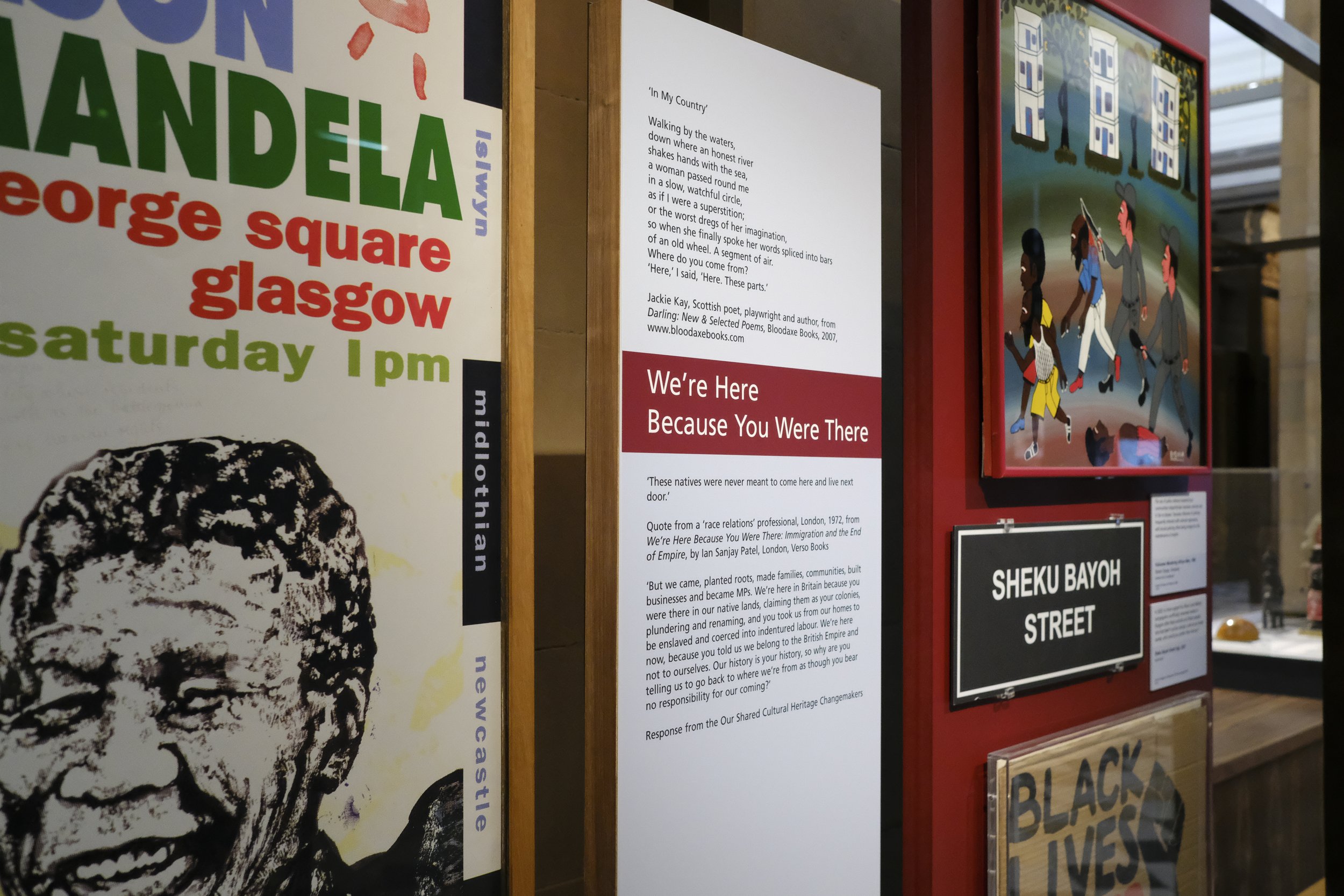

When walking around the City of Empire at Kelvingrove Museum, you are confronted with Glasgow’s colonial past and present: a school desk, a racist children’s book, and a cardboard ‘Black Lives Matter’ sign. These tangible elements are interspersed with multimedia video instalments which further explain the impact of slavery and empire in Glasgow today. While these are heavy subjects, the exhibition has a widely accessible and conversational tone, telling person and community-centred stories.

The exhibition was led by a team of four young people from the ‘Our Shared Cultural Heritage’ (OSCH) Changemakers group: Miriam Ali, Meher Waqas Saqib, Kulsum Shabbir and Sehar Mehmood. These community curators took responsibility for delivering different sections of the exhibition.

I caught up with Sehar who worked predominantly on the section titled ‘We’re Here Because You Were There’, which collates together news articles about brutality and violence towards minority ethnic people in Scotland. Sehar’s work on recontextualising news articles – within a space where they can be observed – encourages viewers to consider and understand the experiences of these communities.

Sehar grew up in Govanhill and has previously written for Greater Govanhill. Her passion for community activism and promoting accessibility in the arts and culture sector is transparent in her work.

“I am a community curator because I’m a member of a community. I think that the word community makes it feel more accessible to everyday people. There is a huge line between the museum and art gallery sector and the public, and it shouldn’t be like that. Museums and galleries have a responsibility to tell stories and to educate the public.”

The City of Empire exhibition is part of an initiative by Glasgow Museums to incorporate underrepresented communities into the work that they do. When asked about the timeline for the project Sehar responded: “It is hard to pinpoint when we started working on the exhibition. It was two years in the making but people have probably been fighting for this since the museum opened in 1901”.

Kelvingrove, much like the rest of Glasgow, has strong links to colonialism. Some of the money earned from the international exhibition of 1888, which was funded by and promoted the empire, was used to open the Kelvingrove Museum in 1901. Sehar told me: “The international exhibition was all about culture, art, science, and travel. It completely exploited human stories and communities.

Despite being erased from social history, Sehar explains that the ties between Glasgow and empire are embedded in the foundations of the city.

“If you want to see the link between Glasgow and slavery just go for a walk. Over 62 streets and areas in Glasgow have a link to empire and slavery, for example, Jamaica Street. It is a systemic issue that museums and schools never talk about.”

Museums have famously been places of appropriation and constructing problematic historical narratives. Sehar rejects the conventions of what an exhibition ‘should’ be and instead relates to a BAME audience by representing lived experience:

“This exhibition is not for the white majority audiences as has always been catered. It’s for people of colour to feel validated and accepted and think ‘We are here.’ My idea was to engage young people and the best way to do this was to give them reminders of their families and communities who came to Glasgow because of colonial violence and the legacies it left in their home country. I wanted to make the exhibitions as relatable and grassroots as possible.”

A key part of making the exhibition accessible was narrating recent history through newspapers. These familiar items have a deeper cultural significance as the media’s language and rhetoric have a notable influence on public opinion.

Read more: City of Empire: Q&A with curators of a new exhibition unveiling Glasgow's colonial legacy

Through self-led research, Sehar used a collage form to display newspaper articles from the trials and murders of Black and South Asian men who were victims of racial violence.

“I get emotional talking about the newspaper collage. I didn’t anticipate how much the research would impact my emotions. I was watching these cases as if they were happening. The museum wasn’t ready for the pain that this caused us because we were learning about violence constantly, violence that has been done to our communities”.

Sehar explains the importance of using language to ensure the exhibition is a collective and accessible space. The exhibition challenges the language we use around slavery and empire and a key consideration in the development of the project was the discourse around the term “minority”.

“In preparation for the exhibition, we decided to use the term ‘people of the global majority’ and I think this is an important choice as the extent of the wider impact is revealed. It is a majority history against a white minority who colonised us. I used the collective pronoun ‘We’ because I wanted the exhibit to feel like it is for us. We, the community, the collective - Govanhill has always made me feel that way.”

Sehar credits the community environment of Govanhill as an inspiration for the exhibition: “I hope the people of Govanhill visit and feel seen and connected to the exhibition. It is not a love letter but an acceptance letter because I see your history. People have forgotten but I won’t forget.”

When you were researching these items, was there anything you found that particularly stood out?

Miriam: The physicality of the object is what stood out to me the most. It felt different to a piece of art as it had a direct link to the farmer of the cotton and the weaver who made the twists. I couldn't find anything behind the process of creating cotton samples and where and when they would have been used but I found the lasting detrimental effect Britain’s trade of Indian cotton has made on India's agricultural environment.

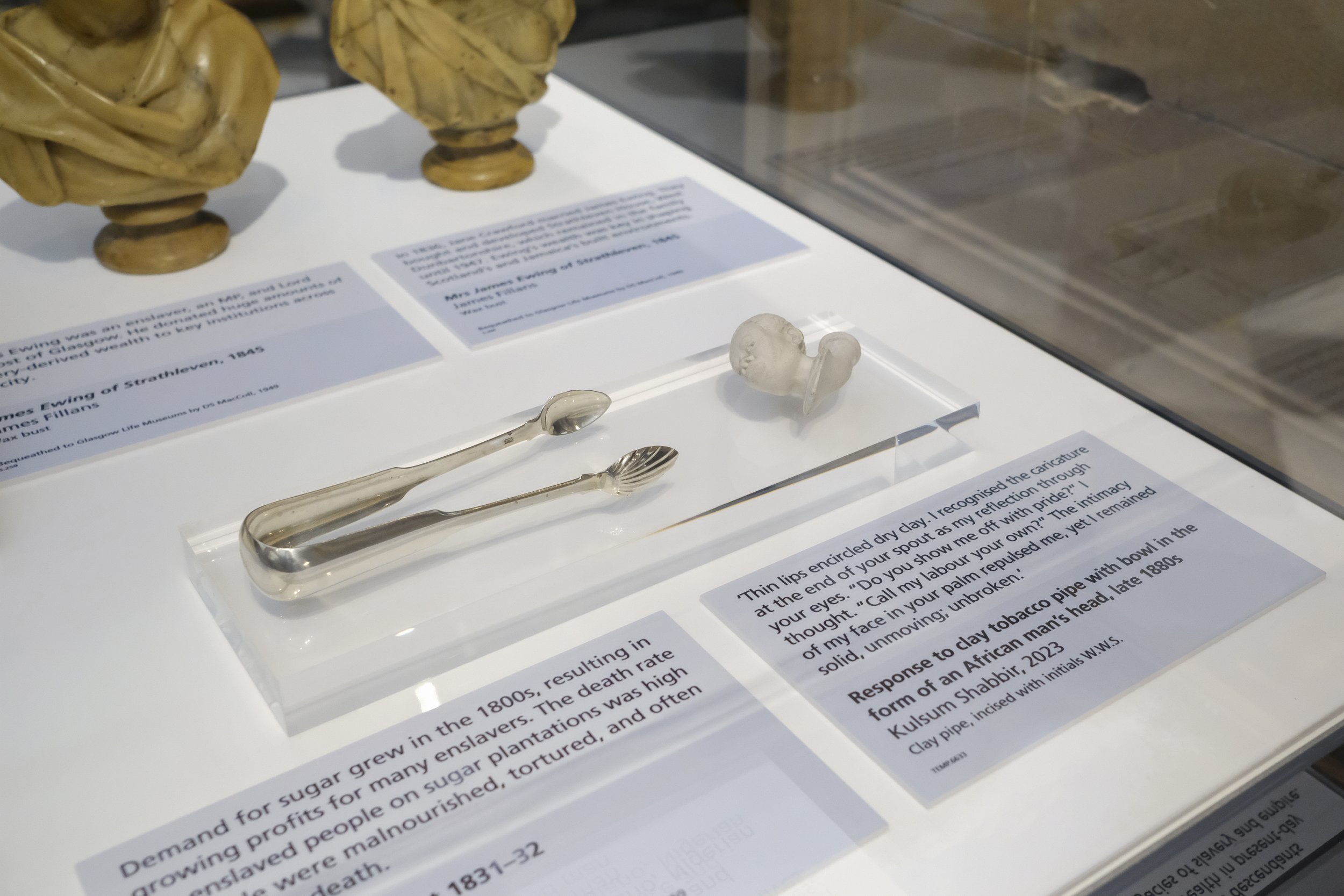

Kulsum: I found little to no information about the tobacco pipe. I felt that this was a reflection of the dehumanisation of enslaved Black people who had their history erased. For the label of this object, I decided to write a short poem from the point of view of the young man depicted, giving a voice to his frustration and strength. The research process for this display could often feel clinical and removed, and being allowed to explore the emotional aspects of such histories was cathartic in a way, and a huge responsibility.

Meher: While exploring Rani of Jhansi's role in the Indian Mutiny of 1857 as a part of the Indian resistance forces, I discovered that the individual leading the British forces against this ‘uprising’ was Colin Campbell, a Scotsman. This underscores the significant and central role that Scots played in British colonial pursuits, shedding light on their deep complicity and leadership in these historical endeavours.

What is unique about this exhibition?

Kulsum: Being involved as a young South Asian person, this experience was invaluable. I gained so much knowledge and experience working on the project, which is exactly the reason I joined OSCH in the first place and I think this is what makes the display so unique. We each brought so much of our personal experience to the project, and I feel that the passion we have for our work is palpable and can be seen throughout the exhibition.

Meher: The addition of cultural aspects, like Urdu poetry into the exhibition is something not done before in a Glasgow Museums exhibition, and this was very exciting for us as it opens the exhibition up to a whole new demographic that may have not visited museums due to accessibility issues.

What do you think audiences can gain by viewing museums through a colonial lens?

Miriam: During a visit with my family, I saw another South Asian family visiting the display. I could see a boy call his mother to come and read something and from what I gathered he was excited to show her the Alama Iqbal poem written in Urdu, next to the Rani of Jhansi statue curated by Meher. This seemingly small interaction is one of the many things we wanted to achieve by being part of this project.

Meher: I hope that it serves as a moment of deep reflection and as a true learning tool. We wanted this whole project to encourage people to view the history of Glasgow in a different way, that acknowledges the struggles and exploitation of people of colour. For people of colour visiting the display, I hope that it brings a sense of familiarity and true representation that has been absent in museums. I would have loved to go into a museum as a child and see my cultural heritage being talked about in a positive light, and truly this project was designed to inspire and educate all people, but especially children. Many issues discussed in the display serve as starting points so viewers are exposed to these issues and can then learn more about them which ensures that the museum serves as an educational space for all.

The City of Empire exhibition is open Monday to Thursday and Saturday, from 10am to 5pm, and Friday and Sunday from 11am to 5pm.