Jasleen Kaur: Alter Altar at the Tramway

Alter Altar is Jasleen Kaur’s latest exhibition at the Tramway. In an interview with Greater Govanhill, the Pollokshields born artist delves into the significance of the exhibition, her connection to Glasgow, the importance of community action and the impact of art on activism.

Words by Samar Jamal | Photos by Paul Watt

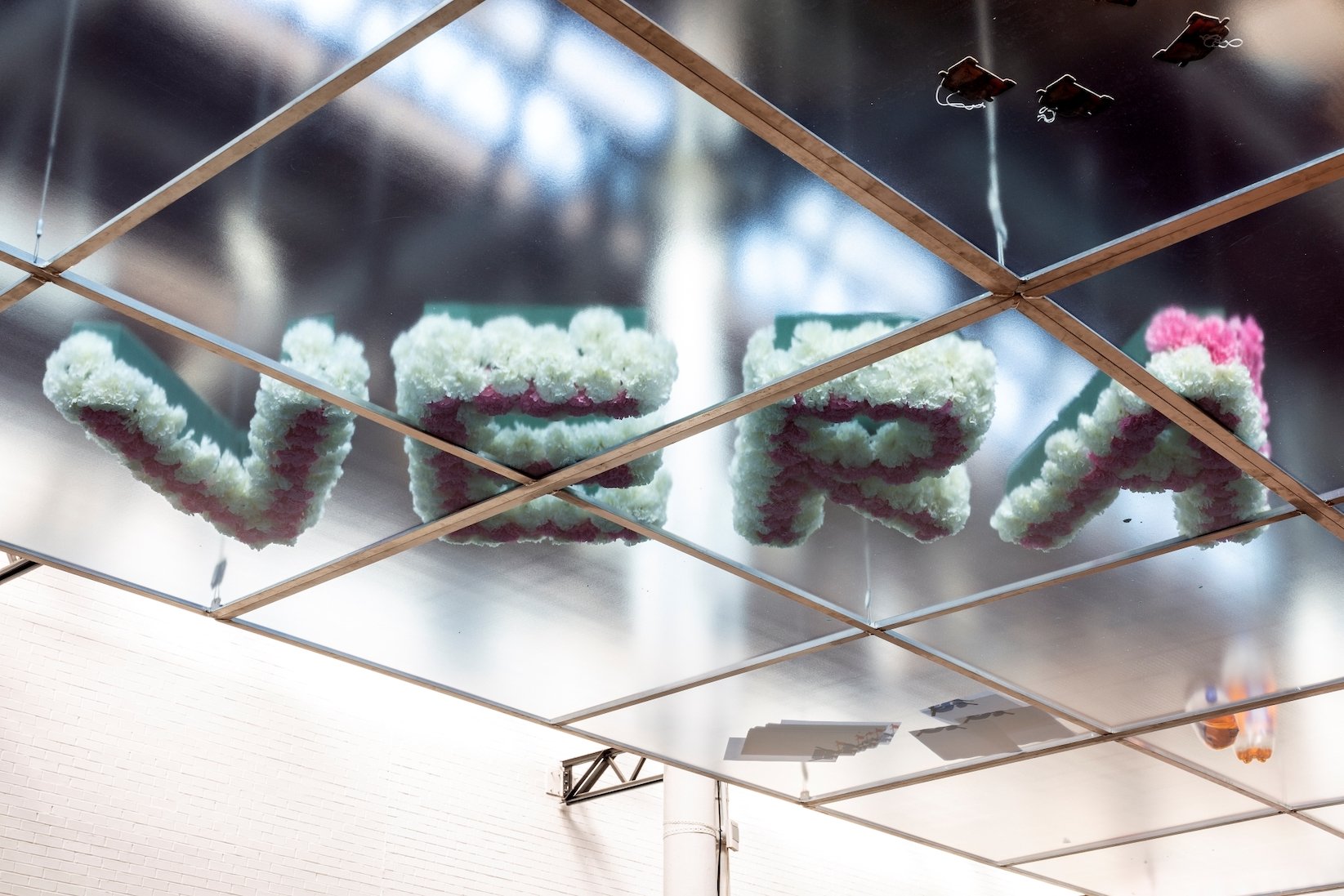

Alter Altar is on show for free at Tramway until the 8th of October. Created by Pollokshields-born artist Jasleen Kaur. It’s an accumulation of two years of work that guides the audience through a mind-altering journey. Many items are an ode to Kaur’s upbringing but also encourage wider thought. Through sounds, bottles of Irn Bru, a football fan scarf, political flyers, a Red Ford car and salvaged family photographs; Kaur’s work alters the ordinary into contemplative thought.

By weaving together significant political and social events, she encourages viewers to ponder their ramifications and the possibility of alternative futures. There is a reference to international events but Kaur’s work also hones into local protests like Kenmure Street. Each element has been strategically included to signify legacies of history and evoke conversations about Empire, nostalgia, culture and more.

In an interview with Greater Govanhill, Kaur delves into the significance of the exhibition, her connection to Glasgow, the importance of community action and the impact of art on activism.

How would you describe Alter Altar in a few words?

Alter Altar is a new body of sculptural and sound work that rethinks tradition and inheritance and finds new routes to lineage. I’ve been thinking in quite a revisionist way, improvising with what is passed down in both a theoretical way, but also practically with the objects and sound work, I’ve made. Improvisation has become a tactic or tool for me to transmute what is inherited. There is a beautiful quote by the South African Jazz musician Asher Gamadze who talks about tradition saying; “I understand tradition as something that emerges through people grappling with their world, there are historical resources that are passed down but everyone is continually improvising and that's how traditions develop.”. This thought was an anchor for my thinking.

As someone who grew up in Pollokshields, how does it feel to have your first exhibition here many years later?

It feels like an honour and came as a total surprise. The questions in the work resonate with so much of the local neighbourhood, my family and this locality was in my mind through the whole process of making the work. The public programme that we developed with local people and organisations means we can welcome residents and groups into the space in a way that feels supported and generative. I’m excited about this.

Alter Altar feels like you are walking through memories that are fond and intimate to you but spread across a vast space. Is there a specific element that you want the audience to begin with?

I’m really open to how someone wants to begin with the work, though the entrance to the space, there are a series of large scale printed images scattered on the floor of solidarity across religious or cultural lines, and an automated harmonium playing intermittently on top of one cropped image, drawing our attention to it. It’s an image of land restitution in Punjab from a Sikh community for a mosque to be rebuilt. I’d like people to think about the images, and what they tell us about how narratives circulate, which are dominant and which are fugitive, which images are mass-produced and which are unseen.

The sounds of music and singing drifting through the room are encapsulating. Particularly as they are not continuous, they grab your attention and support your understanding of Alter Altar. How did you decide on the intervals at which they played?

Very intuitively. I edited the sound in the space during the installation with sound editor Joe Howe. I like the clarity required for an editing process, you get rid of what is not necessary, it’s quite a brutal process but the work becomes a lot clearer by the end of it. It’s very satisfying. I was thinking about how sound might pull your attention around the space and about the sonic resonance of the Gurdwara next door and influenced by modes of communal music making, such as ecstatic chanting or call and response.

Your work touches a lot on themes of community and collective action. Can you expand on what that means and looks like to you?

I think it looks like practising solidarity across borders, cultural and religious namings. Personally, I am drawn to points in my own history or ancestry where there is a blur in named identities, or who was part of a devotional community. The writer Ariella Azoulay calls this ‘potential history’, to look forensically at the past and identify points of other possibility. Specifically in the show, I make reference to the Muslim Rababi-Sikh shared musical heritage which is a largely unknown part of our lineages. For me, these histories act as evidence to counter what we think we know, and how we practice communality today. In this show, I tried to reimagine the space as a temporary, transient space for gathering and holding people. I heard from the curators that it was recently used as a prayer space for a local Muslim community, which felt really special.

Do you think that there are enough facilities and support for someone who wants to pursue an artistic career now in comparison to when you were younger?

It’s a difficult time to study anything in the UK, never mind the arts, so probably no. But more institutions and galleries are showing the work of artists from diverse backgrounds so this is a huge positive and powerful shift.

Glasgow has a unique history and Pollokshields and the nearby areas are constantly striving to use art to communicate critical issues. What are your thoughts on using art as a form of resistance?

The writer Lola Olufemi talks about art as ‘a writing back’ which is such a powerful suggestion — art is evidence of other ways to think and live. But she also writes; ‘Art is powerful, but it is not powerful enough to undo centuries of colonial domination or climate catastrophe’ which is humbling and true, especially under the conditions that most of us are making art, mediated through institutions. The meaningful work happens elsewhere, through a different kind of exchange.

Unfortunately, not everyone is engaged in art. This can be due to financial constraints, lack of resources or perhaps cultural constraints as it is sometimes viewed as a futile practice. How do you think we can better engage people and alter their perceptions of how critical art really is?

The problem is with the art institutions and structures that keep it out of reach and define what art is and who can be an artist. I think our education system is a big factor too, from as young as nursery age there is the schoolification of learning. I think I grew up with loads of art and culture, but it didn’t cross paths with contemporary Western art culture and I wasn’t encouraged to go to art school. Teaching in higher education has made me quite disillusioned too, as to who has access to a career in the arts. They are small steps but it has felt really positive mentoring through programmes such as Scottish Refugee Council or developing the public programme with Tramway, that funds grassroots organisations rather than pander to the art world. It feels like discreet work or diverting resources are good tactics for now.

Alter Altar is a moving exhibition that leaves audiences in transcendent thought. Check it out at Tramway, on display until 8 October.

For additional reading and an expansive breakdown of Alter Altar click here